PEOPLE OFTEN MISTAKE VENUS for a star. After the Moon, it is the brightest object in our night sky. Because it is so close in size to Earth, until the 20th century astronomers assumed that it might be in some ways like Earth. The probes sent to investigate have shown that this is not so. The dense cloudy atmosphere ofVenus hides its surface from even the most powerful telescope. Only radar can penetrate to map the planet's features. Until it became possible to determine the surface features-largely flat, volcanic plains-scientists could not tell how long the Venusian day was. The atmosphere would be deadly to humans. It is made up of a mixture of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid that causes an extreme greenhouse effect," in which heat is trapped by the atmosphere. The ancients, however, saw only a beautifully bright planet, and so they named it after their goddess of love. Nearly all the features mapped on the surface ofVenus have been named after women, such as Pavlova, Sappho, and Phoebe.

Calculating Distances

One way to calculate the distance of Earth from the Sun is for a number of observers all around the world to measure the transit of a planet (the passage of the planet as it crosses the disk of the Sun and appears in silhouette). The British explorer Captain James Cook led one of the many expeditions in 1769 to observe the transit ofVenus from Tahiti. Calculations made from these observations also enabled astronomers to work out the relative measurements of the entire solar system.

Looking at Venus

In 1978 the United States launched the Pioneer Orbiter, designed to map the surface ofVenus by using radar to penetrate its densely clouded atmosphere. It was followed in 1989 by Magellan, which circled Venus every 3 hours and 9 minutes and had a 12-ft (3.7-m) radar dish that beamed radar images back to Earth for analysis. Computers were used to build up pictures of the surface-mainly volcanic plains. This view from space does not show the true color of the planet; a blue filter has been used to emphasize the cloud layers. Another Venus mapper is the large radio telescope near Arecibo in Puerto Rico.

Puzzling Surface

Even with the best telescope, Venus looks almost blank. This led the Russian astronomer Mikhail Lomonosov to propose that the Venusian surface is densely covered with clouds. As recently as 1955, the British astronomer Fred Hoyle (1915-2001) argued that the clouds are actually drops of oil and that Venus has oceans of oil. In fact, the clouds are droplets of weak sulfuric acid, and the planet has a hot, dry volcanic surface.

Assembling Venera Probes

During the 1960s and 1970s the former USSR sent a number of probes called Venera to investigate the surface of Venus. They were surprised when three of the probes stopped functioning as soon as they entered the Venusian atmosphere. Later Venera probes showed the reason why-the atmospheric pressure on the planet was 90 times that of Earth, the atmosphere itself was highly acidic, and the temperature was 900°F (465°C).

Greenhouse Effect

The great amount of carbon dioxide in Venus's atmosphere means that, while solar energy can penetrate, heat cannot escape. This has led to a runaway" greenhouse effect."Temperatures on the surface eaSily reach 870°F (465°C), even though the thick cloud layers keep out as much as 80 percent of the Sun's rays.

Landing on Venus

This image was sent back by Venera 13 when it landed on Venus in 1982. Part of the space probe can be seen at bottom left and the color balance, or scale, is in the lower middle of the picture. The landscape appears barren, made up of volcanic rocks. There was plenty of light for photography, but the spacecraft succumbed to the ovenlike conditions after only an hour.

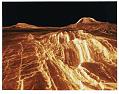

Three-Dimensional View

This radar image of the Western Eistla Region, sent by Magellan, shows the volcanic lava flows (see here as the bright features) that cover the landscape and blanket the original Venusian features. Most of the lahdscape is covered by shallow craters. The simulated colors are based on those recorded by the Soviet Venera probes.

Facts About Venus

- Sidereal period 224.7 Earth days

- Surface temperature 870°F (465°C)

- Rotational period 243.2 Earth days

- Mean distance from the Sun 67 million miles/108 million km

- Volume (Earth = 1) 0.86 • Mass (Earth = 1) 0.815

- Density (water = 1) 5.25

- Equatorial diameter 7,520 miles/12,100 km

- Number of satellites a